Urban greenery, parks, tree canopies, green corridors, and urban forests are far more than aesthetic frills. It is the foundational infrastructure for sustainable cities. In Balkan green cities, this agenda encompasses both climate policy and quality-of-life policy, addressing heat, health, mobility, and equity in a single stroke. Greenery regulates microclimates and mitigates urban heat islands, filters air pollutants, and supports stormwater management, reducing flooding and improving resilience. On a human level, access to green spaces is linked with lower stress, enhanced mental health, and increased physical activity, delivering both social and public health dividends. Even a few square meters of green per person can significantly boost well-being. While the WHO recommends at least 9 m² per capita, many cities fall short, underlining the urgency of more equitable green distribution.

Key takeaways across eight capitals: total green infrastructure is highest where municipal borders include forests or mountains, but accessible, walkable green inside dense districts lags behind; corridor-first strategies (rivers, wedges, linear parks) are the fastest lever to close the gap.

Profile of greenery in Balkan capitals

Across the Balkans, topography and planning histories shape today’s green balance sheet. Mountain-front cities like Sofia and Sarajevo inherit large peri-urban natural assets (Vitosha; steep, forested hills), but access within the dense cores can be patchy. Postwar Belgrade and Skopje were recast with modernist super-blocks and inter-block open space; decades of infill have since eroded that “tower-in-the-park” legacy. Tirana’s fast urbanization after the 1990s left gaps in formal parks but also created room for “metrobosco” belts; Zagreb retains a 19th-century green identity anchored by Lenuci’s “Green Horseshoe”. These path-dependencies help explain why some capitals report impressive green per capita figures when entire administrative forests are counted, yet struggle to meet neighborhood access standards in everyday life.

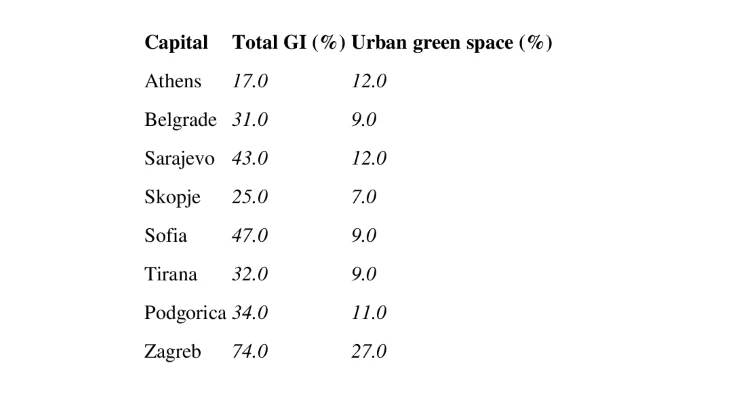

Table 1. Percentage of total green infrastructure (GI) and urban green space (UGS) (Values are shown to one decimal place, rounded from the Green Infrastructure dashboard (2021) baseline)

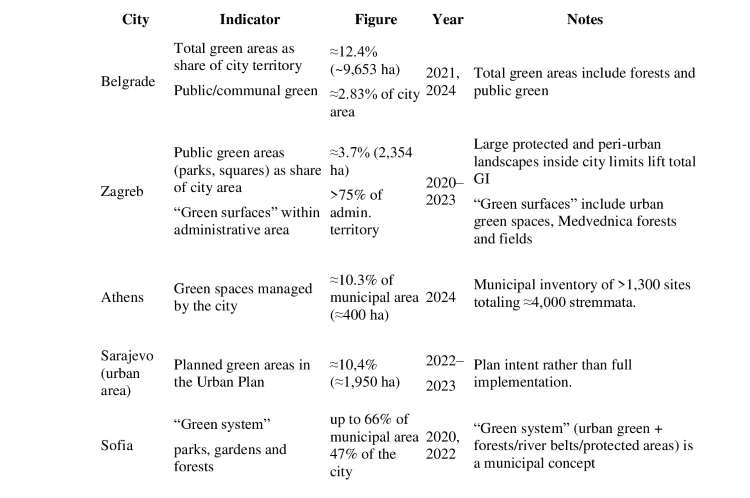

Table 2. Comparative snapshot: city-level/official greenery metrics.

Sources: GCAP (Belgrade, 2021), Стратегиjа зелене инфраструктуре града Београда (2024), Zelene površine – stvarno korištenje površina (2023), Zagreb u brojkama (2018), This is Athens , Δήμος Αθηναίων (official municipal website), Zeleni akcioni plan kantona Sarajeva, GCAP (Sofia, 2020), The Sofia 2030 agenda

Calculation note: Where official sources listed only surface area but not a percentage, we derived “% of municipal area” as (reported green area ÷ municipal land area) × 100, using the administrative municipality as the denominator, converting units where needed (1 stremma = 0.1 ha), and rounding to one decimal; we kept each city’s own scope (e.g., public green vs green system), so figures reflect local definitions rather than a reclassification. Example: in Athens, about 3.9–4.0 km² of city-managed green over 38.96 km² yields roughly 10.0–10.3%.

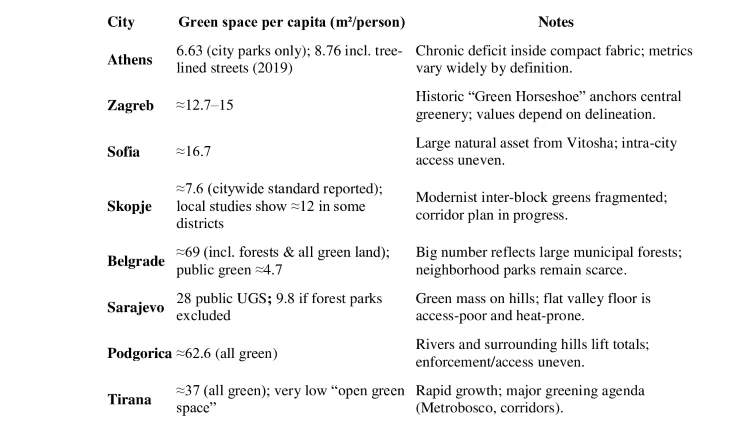

Table 3. Green space per capita (methods differ; see footnote). Primary column in m²/person; alternate KPI shown where used locally.

Sources: City of Athens Climate Action Plan (2022), Gradska zelena infrastruktura u Zagrebu (2021), European Commission profile, , Green City Action Plan of Sofia (2020), Студиjа за воспоставување на зелене коридоре (2017), Green City Action Plan of Skopje (2020), Green City Action Plan for City of Belgrade (2021), Mogucnosti primene ekološkog indeksa u planiranju Beograda (2022), Assessing green space indicators: A case study of Sarajevo (2024), Smart Sustainable Cities Profile Podgorica, Green City Action Plan of Tirana (2018)

Reading Tables: Total GI is broad (public parks + private gardens + forests + water/wetlands + HNV farmland); UGS is a narrower, accessible subset (parks, urban forests, cemeteries). Shares refer to administrative area, not FUAs. For per-capita metrics, the most policy-relevant comparator is public/accessible green. Conversion note: 1 ha/100,000 people = 0.1 m²/person.

Cities, geography, and traditions: how place shapes urban nature in the Balkans

Athens is a basin city framed by mountains, so growth has long been squeezed inward and upward. Postwar antiparochi swapped small plots for apartment rights and filled the city with polykatoikia blocks, a vernacular of balconies and tiny squares that delivered housing at speed but left few large parks. Rivers that once breathed through the grid, like the Ilisos, were buried under traffic, while today the metropolis leans on distant reservoirs (Mornos, Evinos, Yliki, and Marathon) for its water. The result is a fine-grained, overheated fabric where parks are unevenly distributed across the city’s seven districts, and large green areas can be hard to reach for the elderly or children. The tradition to build on is already there—street trees, courtyards, neighborhood squares; the task is to turn that improvisational green into a connected shade that carries the mountain breezes into everyday streets.

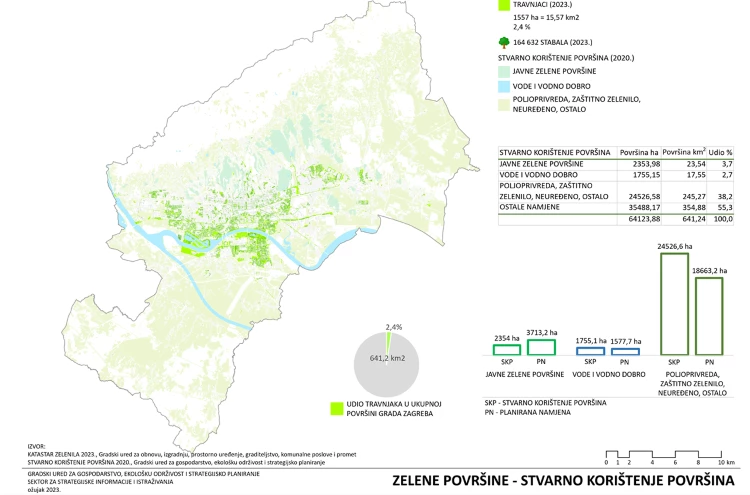

Zagreb grew up with a municipal gardening culture that predates most modern planning: Maksimir’s 19th-century park ideals, Milan Lenuci’s Green Horseshoe, and a civic habit of street trees and squares that make promenading a way of life. Even post-war expansions across the Sava carried DNA superblocks framed by lawns and playgrounds. The contemporary challenge is classic Zagreb: keep the thread unbroken so new districts read as chapters in the same green story rather than detached cul-de-sacs.

Source: Katastar zelenila

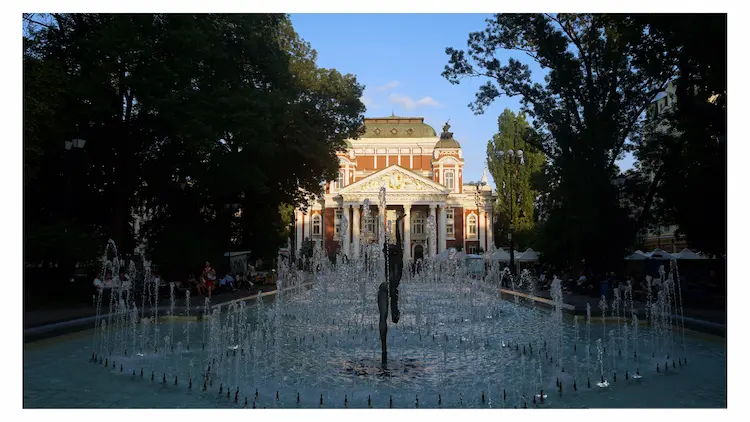

Sofia’s self-image has long been a “city with a mountain,” and planning traditions tried to make that literal—from interwar green wedges that pointed at Vitosha to socialist-era microdistricts designed with shared courtyards and generous setbacks. The trouble is distribution: the mountain’s abundance and the inner ring’s needs have seldom met. Today’s task revives the old ambition to draw the mountain into corridors, schoolyards, and tram routes, so that everyday Sofia can inherit what the skyline has always promised.

Sarajevo is an amphitheatre of green ridges around a tightly built valley. The city layers Ottoman mahalas and Austro-Hungarian avenues into a tight basin city where hillside cemeteries and forests are both memory and green structure. The topography lifts the headline share of nature but also concentrates accessible parks into only a few corridors on the flat. That geography–equity split is exactly what the tables capture: abundant landscape capital on the slopes, thinner neighbourhood green where most people live and work. Cooling the valley floor without sacrificing the intimacy that makes Sarajevo’s streets so magnetic will require a lattice of small, near-home interventions.

Belgrade sits at a grand confluence, with rivers and municipal forests that inflate the “total green” picture. Walk that back to the scale of everyday life, however, and the city-official metrics show the pinch: modernist super-blocks once framed generous inter-block lawns, but decades of incremental infill have gnawed at those commons. The new green-infrastructure push has the right diagnosis; success will hinge on protecting what remains, reconnecting it across wide roads, and treating riverbanks as climate spines rather than just real-estate frontiers.

Skopje is a valley city that has paved itself into the heat and still air. Its modern identity was forged after the 1963 earthquake, when reconstruction plans laid out wide boulevards, inter-block open space, and a river spine meant to ventilate the valley. The EEA table places it mid-pack, but the local datasets and planning targets make the point more plainly: without green corridors along the Vardar and its tributaries, the fragments will never add up to comfort. Here, nature has to be engineered back into the grid boulevards that carry trees and wind, schoolyards that double as rain gardens, inter-block lawns that are safe from the death-by-a-thousand-parcels.

Podgorica’s urbanism has always negotiated rivers and low hills (Morača, Ribnica, Gorica, Ljubović), so the local idiom of “park-forests” feels natural rather than imported. Older neighbourhoods kept yards and tree-lined streets; later blocks added wider setbacks and green pockets that soften Mediterranean summers. For a smaller capital, stewardship is the comparative advantage: keep cadastres current, invest in care, and push shade to bus stops and everyday routes where heat is least forgiving.

Tirana’s civic axis, Italian-era boulevards, a culture of evening promenade, and a lakeside park that became the city’s collective backyard, gives it a public-space tradition to build on, even after the tumult of 1990s growth. The new playbook is a conscious return to structure: an orbital belt to hold the edge, linear parks and shaded boulevards to braid green through dense quarters, and pocket spaces where informal fabric needs relief. The goal is simple: turn a proud street life into a cooler one.

Projects advancing urban nature in Balkan green cities

Athens. On the coast, the Ellinikon (you can read about it here) is the city’s flagship green retrofit; its first public areas opened as the Ellinikon Experience Park and the wider metropolitan park is phasing in as part of the Athens Riviera regeneration (under implementation). Inland, the Great Walk of Athens (Μεγάλος Περίπατος, launched 2020) reclaims a historic east–west axis for walking and cycling, tying together the archaeological core and key civic boulevards.

Zagreb. The city’s SECAP – Sustainable Energy and Climate Action Plan elevates green infrastructure from amenity to adaptation (in force), while the municipal horticulture utility Zrinjevac (a division of Zagrebački holding) does the everyday work of tree care, pocket-park infill, and play-space upgrades, along the legacy spine that includes Maksimir (ongoing).

Sofia. A corridor-first approach aims to “pull the mountain into the city.” Green Sofia and Sofiaplan are reviving the historic green wedges (зелени клинове) and piloting a health-oriented green corridor in Nadezhda under the EU H2020 URBiNAT project (2019–2024 pilot complete; follow-up actions ongoing). Complementary municipal initiatives include the long-running New Sofia Forest (Нова гора на София, since 2018) and active street-tree programs.

Belgrade. Policy has caught up with projects. The The Green Infrastructure Strategy of Belgrade (2025–2032) was adopted by the City Assembly at end-2024 (in force), defining standards and budgets for trees, roofs, riverbanks and inter-block greens. In parallel, the 4.6-km Linijski park (Linear Park) is under construction in phases along the former riverside railway, stitching Dorćol to the Sava–Danube confluence. Together, the “system-plus-spine” model targets heat, access and riverfront microclimates.

Skopje. A valley city writes a corridor playbook. The Study for Establishing Green Corridors (2017) along the Serava and Lepenec to the Vardar set the alignments; the city’s climate strategy and Green City Action Plan scale those into policy, with staged implementation focused on ventilation, shade and active mobility along rivers and boulevards.

Sarajevo. The canton pairs its The Green Cantonal Action Plan (2021–2031) with a dedicated chapter on urban ventilation corridors, a technical basis for tree-lined tram and river routes across the valley floor, where exposure and footfall are highest.

Podgorica. Stewardship meets block-by-block care. The Management Plan for the Park-Forest Gorica (2024–2029) formalizes protection, thinning, replanting and access upgrades for the city’s signature hill-forest (adopted 2024). Municipal utility Zelenilo d.o.o. backs this with seasonal planting and neighborhood park works, including upgrades around Ljubović park-forest (works ongoing).

Tirana. The TR030 General Local Plan (adopted 2016–2017; in force) sets out the Pylli Orbital / Metrobosco (Orbital Forest) as a growth-management and cooling belt, while the New Boulevard (Bulevardi i Ri) and ongoing Grand Park (Artificial Lake) upgrades build an inner green network. The city’s GCAP flags the deficit in open public green and links the belt to corridors to translate totals into everyday access.

Recommendations for greener Balkan cities

Do now, 0–12 months.

- Adopt a corridor-first playbook: identify and protect river, ridge and ventilation corridors; design quick-build shade on priority walking routes and school streets. Governance lever: street design code + interim design permits. Who pays: municipal CAPEX and EU recovery/Green Cities grants.

- Protect what you have: halt permitting that nibbles inter-block greens; designate heritage parks and peri-urban forests as climate infrastructure. Governance lever: zoning overlays + tree ordinances. Who pays: municipal OPEX; PPPs for maintenance.

- Standardize metrics and publish them: one dashboard per city tracking UGS %, m²/person, canopy and access within a 10-minute walk. Governance lever: citywide green cadastre; open data. Who pays: municipal digital budget and donor support.

Within 2–3 years.

- Build connective tissue: linear parks, green wedges, and shade-first boulevards linking hills/water to the core; retrofit schoolyards as rain gardens. Governance lever: capital works program aligned to SECAP/GCAP. Who pays: EU cohesion funds and IFI loans.

- Incentivize private greening: green roofs/walls on large footprints; biodiversity-positive retrofits tied to building permits. Governance lever: density bonuses; fee-in-lieu earmarked for parks. Who pays: developer contributions and green bonds.

- Professionalize care: tree nurseries, seasonal planting, and inter-departmental maintenance teams (transport, parks and utilities). Governance lever: service-level agreements. Who pays: municipal OPEX and PPP service contracts.

Closing reflection

Cities are living ecosystems, and urban green infrastructure is not merely decorative but essential infrastructure for health, resilience, and equity. Across the Balkans, there is both promise and peril: from the green excellence of Zagreb to the nascent yet inspiring growth in Athens and Tirana.

For Balkan green cities, the shift becomes durable when plans name the strategy, fund the corridors, and embed maintenance so that green shows up not only on satellite charts, but on Tuesday afternoons under trees that meet overhead on the school run.

Read more about sustainable development in the Balkans here.