Today, almost all of our cities regret their transport systems, with too much space allocated to cars, excessive congestion and pollution and diminished liveability. Many are desperately trying to reclaim their streets from the tyranny of the motor vehicle. Will autonomous vehicles and sustainable cities coexist, or will AVs become an obstacle to liveability?

AVs are coming. We do not know how quickly they will be deployed or what setbacks they will encounter, but they are coming. Whilst a lot of the discussion on AVs focuses on the technology, safety concerns or job impacts, as a transport strategist, I’m primarily concerned with their effect on our transport systems overall and whether we will have better or worse cities as a result.

Two scenarios for autonomous vehicles and sustainable cities

The nightmare scenario is that we replace human-driven, privately owned vehicles with privately owned AVs, making car travel easier, inducing demand for car use, and creating more congestion in our cities. For people who currently use public transport, they will be offered a service at a similar price, except that it picks them up at their door, without the need to share with others and drops them off at their destination, destroying public transport as ridership and revenues plummet. This exacerbates congestion, as all these people requiring drop-off and pick-up will demand vast spaces for these zones, forcing cities to allocate ever more space for cars and less for people.

On the other hand, the dream scenario is that we utilise AVs to create better transport systems by supporting connections to public transport, while shared robotaxis reduce private ownership. This frees up space used for cars, and provides more space for alternative modes such as cycling infrastructure and dedicated bus lanes. We can also replace car parks with human-oriented uses, such as housing and amenities.

Already today, different cities are experimenting with autonomous transport — and their approaches show which scenario may unfold.

For example, in Singapore, robotaxis have been tested since 2016 to serve the “first and last mile” to metro stations, integrating AVs with public transit rather than competing with it. In Phoenix, USA, Waymo already operates a large-scale driverless ride-hailing service. Early evidence suggests that people are using it mainly as a substitute for human-driven taxis rather than giving up private cars — underlining the risk of reinforcing car dependency. In Stockholm, a congestion pricing system has been in place for years, successfully reducing traffic volumes and air pollution. This shows how smart road pricing can influence driver behaviour — a lesson that will be crucial in the AV era. Yet with current policy settings in most jurisdictions, we are moving toward the nightmare scenario. The pressing question is: how do we avoid it?

Two Essential Tools

We do not need to reinvent the wheel; the tools we require are already available. What matters is how we apply them to achieve the outcomes we want. In fact, only two are essential: the transport mode hierarchy and road pricing.

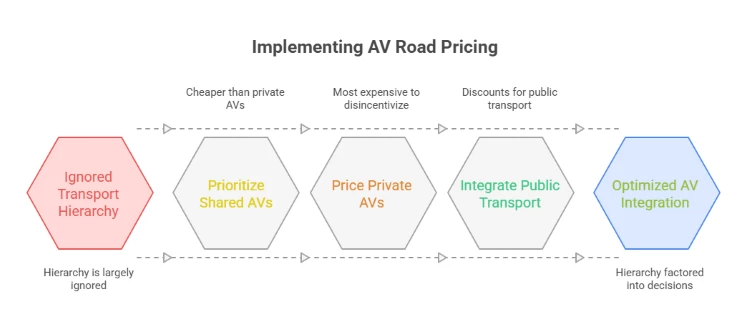

The transport mode hierarchy ranks modes according to sustainability, safety, and efficiency. At the top — and therefore the highest priority — is walking, followed by cycling, e-bikes, public transport, car sharing, and finally private vehicles.

This hierarchy should be adapted to account for AVs, while preserving its core principles. Shared AVs or robotaxis would rank slightly above human-driven car sharing, thanks to the expected safety benefits of removing the driver. Privately owned AVs would be positioned above conventional private vehicles for the same reason.

In practice, however, the hierarchy is often codified in official guidance but widely ignored. That is where the second tool becomes vital: road pricing.

Road pricing charges users for access to road space. It remains highly controversial, and only a few jurisdictions have implemented it in any form — usually limited to congestion zones rather than the entire road network. So why would road pricing be more acceptable in the case of AVs? Precisely because it is crucial to get ahead of the curve.

Some jurisdictions already apply road-user charges to electric vehicles (EVs). This has proved less contentious, as EVs represent only a small share of the fleet and disparities in fuel tax are broadly recognised. For AVs, introducing a road pricing framework before mass deployment would face little resistance. As AVs become widespread, people will naturally incorporate usage charges into their decisions. Critically, shared AVs should be priced lower than private AVs — but higher than public transport — with discounts for seamless connections to transit. Private AVs should remain the most expensive option, to discourage their use and avoid undermining collective mobility.

Addressing Objections

Some will argue that raising costs to discourage AV use could slow adoption and delay potential safety benefits. This may well be true. Yet the long-term costs of congestion and ever-growing demands for road infrastructure justify a more measured pace of introduction.

Equity concerns may also be raised with regard to road user charges. But it is far more effective to provide targeted support for low-income groups to meet their transport needs than to subsidize road use for everyone equally.

Others will contend that people should be free to choose whichever mode best suits them, and that policymakers should not attempt to engineer a top-down utopia. Freedom of choice is indeed important. But at present, many desired options — such as safe and sufficient cycling infrastructure — are underprovided, while car infrastructure is heavily subsidized. These subsidies distort choices and entrench car dominance. Removing them would in fact expand freedom, not reduce it.

Conclusion: autonomous vehicles and sustainable cities in 2050

AVs offer potential societal benefits but risk making cities more car-dependent, demanding more space for cars, increasing congestion, and reducing sustainability and liveability. We must implement policies now to avoid these scenarios, enabling us to reclaim space from cars and create more liveable, sustainable cities.

Imagine a typical city street in 2050. Parking lots have almost disappeared, replaced by small housing blocks, cafés, and playgrounds. Where rows of cars once stood, there are now green boulevards and cycling highways, while fleets of autonomous shuttles circulate as feeders to metro and tram lines.

A central lane is reserved for on-demand robotaxis, but they operate under strict priority rules — public transit and cycling come first. The street is quieter and cleaner: noise and emissions have dropped, and sidewalks are wide enough for outdoor cafés and strolling.

Such a city is not only more convenient but also fairer: people without private cars gain more mobility, and children and the elderly feel safe in public spaces.

About the author: Russell King is editor of the Transport Leader Newsletter and Blog