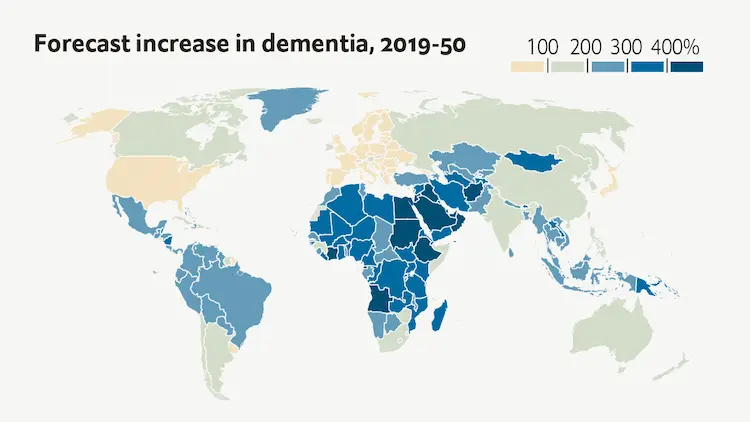

Mental health has become one of the defining challenges of the 21st century. As societies urbanize and populations age, conditions like Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and dementia are rising sharply, reshaping healthcare systems and global well-being. Today, scientists increasingly warn that air pollution raises the risk of dementia, linking long-term exposure to pollutants with accelerated cognitive decline. This growing body of evidence demands a deeper look at how our cities, infrastructure, and environmental policies directly influence brain health.

Aging populations, rising disease burdens: why the issue is urgent

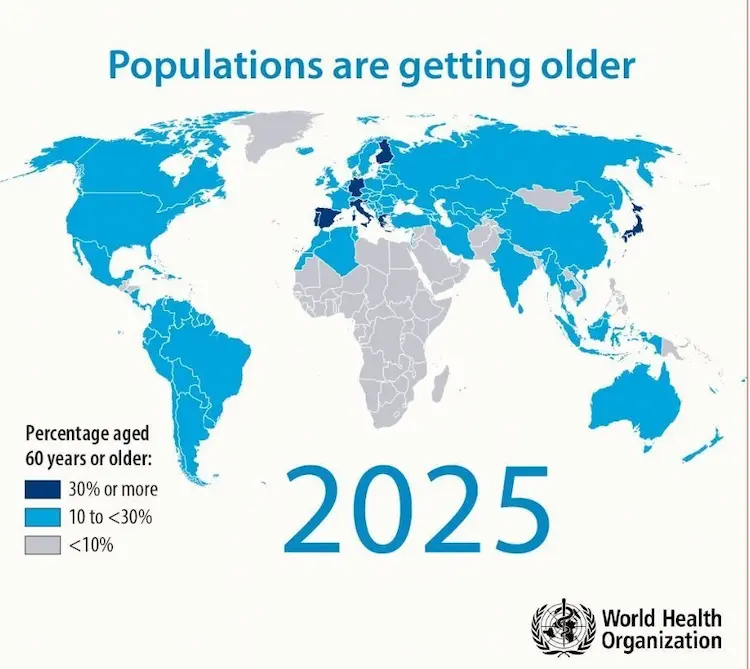

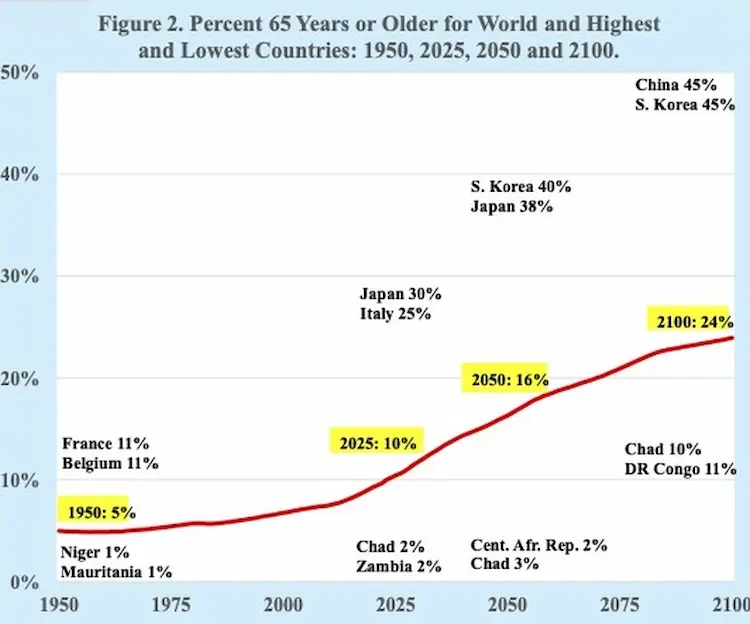

According to the World Health Organization, the world’s population of people aged 60+ will double by 2050, reaching 2.1 billion. As societies live longer, neurodegenerative diseases are becoming a major global health burden:

- 55 million people currently live with dementia, and nearly 10 million new cases occur every year.

- Alzheimer’s disease accounts for 60–70% of dementia cases.

- The prevalence of Parkinson’s disease has more than doubled in the past 25 years.

Age remains the strongest predictor of these conditions, but environmental exposures are increasingly recognized as significant modifiers of risk. As the older population grows fastest in cities, where air pollution levels are typically highest, the need to understand environmental drivers of neurodegeneration has become urgent for planners, health systems, and policymakers.

Air pollution raises risk of dementia: inside the landmark global study

One of the most comprehensive global investigations into this connection is the planetary study led by researchers at the MRC Epidemiology Unit at the University of Cambridge, with support from the European Research Council (via Horizon 2020) and the European Union’s Horizon Europe Programme.

In total, the team reviewed 51 independent epidemiological studies, covering data from more than 29 million participants, making this, to date, one of the largest global efforts to systematically assess air pollution’s impact on cognitive health. From these, 34 studies met sufficiently rigorous criteria and were included in the formal meta-analysis. The geographic spread was wide: 15 studies from North America, 10 from Europe, 7 from Asia, and 2 from Australia.

The studies varied in design; many were long-term cohort studies that used data from population registries, health records, and environmental monitoring linked to participants’ residential locations. In this way, participants’ cumulative exposure to outdoor air pollution over years or decades was estimated, rather than just short-term exposure.

The meta-analysis focused on common urban/industrial air pollutants known to penetrate deeply into the body:

- Fine particulate matter (PM₂.₅): tiny airborne particles ≤ 2.5 microns in diameter, produced by vehicle exhaust, power plants, industrial processes, wood-burning stoves/fireplaces, construction dust, and also formed via atmospheric chemical reactions.

- Nitrogen dioxide (NO₂): a byproduct of fossil-fuel combustion: from traffic (especially diesel), industrial emissions, gas stoves/heaters.

- Soot / black carbon (“soot particles” measured as part of PM₂.₅ absorbance / related metrics): again largely from traffic exhaust and combustion sources (wood burning, industry).

The analyses estimated average long-term exposure levels (over years) for each participant, reflecting the pollution present in their area of residence. This method is more meaningful than short-term snapshots, because neurodegenerative processes likely develop over decades, chronic exposure matters more than isolated high-pollution episodes.

Key findings: how air pollution affects brain health

Across continents and age groups, the study revealed several major outcomes demonstrating how long-term exposure to polluted air increases vulnerability to dementia and related neurodegenerative conditions.

Long-term exposure significantly increases dementia risk

Even moderate increases in PM₂.₅, fine airborne particles capable of reaching the bloodstream and the brain, were associated with markedly higher rates of dementia diagnosis. In some of the strongest studies reviewed, the risk rose by up to 17% for each 2 μg/m³ increase in long-term PM₂.₅ exposure.

Nitrogen dioxide (NO₂) also elevates risk

The analysis found that NO₂ exposure was associated with a 3% higher risk of dementia, reinforcing concerns about pollutants produced by burning fossil fuels, particularly diesel vehicles, industrial activities, and household gas appliances. This finding aligns with a growing body of research showing that traffic-related emissions are among the most harmful for long-term cognitive health.

Soot and black carbon show strong associations

According to the evidence synthesised in the review and highlighted in independent reporting, soot particles, especially those originating from vehicle exhaust and wood burning, were linked to a larger impact: a 13% increase in relative dementia risk. These ultrafine particles are highly potent because they can penetrate deeply into the lungs, enter the bloodstream, and reach the brain, contributing to inflammation and vascular damage.

Taken together, these findings underscore that air pollution is a modifiable environmental risk factor with profound implications. As Dr Christiaan Bredell from the University of Cambridge noted, dementia prevention cannot rely on healthcare alone; it requires coordinated action across urban planning, transport policy, and environmental regulation, since the quality of the air we breathe is shaped by the cities and infrastructures we build.

One atmosphere, one responsibility

The evidence is clear: air pollution raises the risk of dementia, and its consequences will only intensify as populations age. This is not just a medical issue; it is a planning, governance, and environmental justice challenge. City leaders, transport planners, architects, and environmental regulators must work together to reduce pollution at the source, redesign cleaner mobility systems, expand green infrastructure, and protect the most vulnerable populations. Because the air we breathe is shared by everyone, and safeguarding brain health begins with safeguarding the atmosphere we all inhabit.

Read more about age-friendly city here.