Sustainability has become a buzzword — a lifestyle, even. So much so that “sustainability specialists” now appear in every industry, many of them coming from backgrounds that have little to do with sustainability. Brands of all kinds market themselves as environmentally conscious, often showcasing a green logo, a healthy-looking leaf, or an “eco-friendly” tag. But what does sustainability really mean, and how to spot greenwashing in a world where almost every brand claims to be green?

The illusion of progress

According to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary, “sustainable” means “capable of being sustained” or “relating to or being a method of harvesting or using a resource so that the resource is not depleted or permanently damaged.” Yet we continue to see drilling for oil, fracking for natural gas, and coal mining promoted as part of “greener” energy strategies. This contradiction raises important concerns.

It’s tempting to believe that companies have discovered miraculous new technologies or that finite resources have suddenly become renewable. But more often, the reality is simpler: we’re being misled.

Global research shows that consumers are increasingly willing to pay more for sustainable products. Forbes recently cited a study by Wharton Business School in Pennsylvania, noting that nearly 90% of Gen X consumers said they would spend an extra 10% or more on sustainable products. Another study, reported by Business Wire, found that over 30% of global consumers were happy to pay more for greener alternatives.

Brands are responding to this shift. But instead of truly transforming their practices, many are adjusting their language and visuals to fit a narrative that sells. Appearing sustainable has become a competitive advantage — even if the substance behind the claims is questionable.

Packaging the message

Consider Scotch’s “more environmentally friendly” version of its classic Magic Tape. With over 65% recycled or plant-based materials, a green leaf on the box, and free samples distributed to positive online reviews on the website, it feels like progress. Users praised the product with statements like: “Price is similar but it is GREEN!”, “This tape is good for the environment and the tape holder is refillable too,” and “Lastly, it helps save the environment being it is plant-based.” But ultimately, it remains a single-use plastic product in a plastic dispenser.

This is a common pattern: a small improvement is highlighted to give the impression of a major environmental breakthrough. Consumers are encouraged to feel that buying “green” is inherently beneficial — that consumption itself is a solution. But true sustainability starts not with better buying, but with less buying — refuse, reduce, repurpose.

Refillable products are another popular example. Many brands offer pouches to refill soap or detergent bottles, marketed as a way to reduce plastic waste. However standard bottles for soap and shampoo are typically made of HDPE, which is widely recyclable, even into similar products. Refill pouches, however, are made from multi-layered materials that combine different plastics with aluminium, making them nearly impossible to recycle mechanically. These pouches often end up incinerated, landfilled, or chemically converted back into fuel by melting them. Ironically, producers are encouraging you to reduce your environmental impact by replacing a recyclable plastic bottle with a single-use, non-recyclable plastic alternative.

So is this a sustainable solution, or a clever marketing gimmick?

The rise of the sustainable product has lead also to the rise of misleading environmental claims, with 2020 research revealing that over half were potentially deceptive, 40% unsubstantiated, and many backed by little to no evidence or verification.

The shift toward accountability

As concern grows around misleading claims, governments are beginning to act. The European Union, for example, has proposed legislation under the Green Claims Directive that requires companies to substantiate environmental claims with independently verified evidence. Originally proposed in March 2023, the directive aims “to prevent greenwashing by requiring companies to substantiate their voluntary green claims in business-to-consumer commercial practices, by complying with a number of requirements regarding their assessment”. This aims to ensure that when a product is labelled “eco-friendly” or “climate neutral,” those claims are backed by science, not just marketing spin. However, the fate of the Green Claims Directive has not been sealed. Recently the European People’s Party (EPP) issued a letter to ask that the directive be reconsidered and ultimately withdrawn.

Outside of the EU, other countries have added their own greenwashing regulations. For example, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission’s guidance on environmental claims, China’s enforcements on advertising language, and South Korea’s Amendment to Environmental Technology and Industry Support Act.

Beyond government efforts, independent certifications like B Corp, Cradle to Cradle, and the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) offer more rigorous standards for sustainability and ethical business practices. However, even these are not immune to criticism and require vigilant third-party audits to maintain credibility. For example, with B Corp, companies self-assess based on the framework provided for the certification. This allows them significant leeway and questions the credibility of the answers put forth.

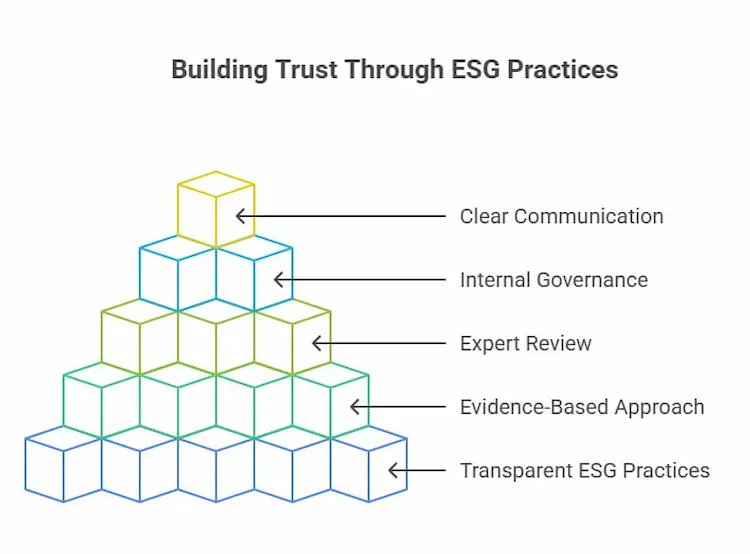

To build real trust, firms must commit to transparent ESG practices, backed by evidence, expert review, internal governance, and clear communication. Vague language, selective comparisons, and omission of critical facts only erode credibility.

These changes — both regulatory and internal — are steps forward. But they also highlight how easily brands have been able to operate in a grey zone of “green” marketing for years. For real progress, policy must be coupled with public education, media literacy, and stronger enforcement mechanisms.

The bigger picture

At the end of the day, the power still lies with the consumer. By learning how to spot greenwashing, we become better equipped to drive demand for honest, sustainable solutions. Before making a purchase, it’s worth asking:

- What is this brand actually doing for the planet?

- Is their story worth your money?

- Or are you just buying into a carefully curated illusion?

True sustainability is not a branding strategy. It’s a complete shift in how we think about growth, production, consumption, and waste. It’s about transparency and accountability — about choosing long-term planetary health over short-term profit.

As long as sustainability is treated as a label rather than a transformation, we risk confusing green aesthetics with green ethics — and that difference may determine whether we secure a livable future or face an irreversible one.

Read more about energy transition here and about ESG reporting here.