Urban swimming isn’t a new idea. Ancient civilizations built public baths as places of hygiene, ritual, and community. But the modern harbor bath is something different; it is a blend of public space, environmental restoration, and urban design. In an era when extreme heat waves have become a frequent hazard for cities, city harbor swimming offers not just recreation but real urban relief, helping the city “ to breathe” during high temperatures. These facilities are built directly on rivers, lakes, and harbors, offering filtered or naturally clean water, lifeguard supervision, and changing facilities, transforming waterfronts into cooling sanctuaries for residents and visitors alike.

From dirty docks to swimming spots

The concept took root in Northern Europe, where cities began reclaiming their polluted waterways. As heavy industry retreated, prime waterfront land was freed up, and stricter environmental regulations spurred large-scale clean-up efforts. What were once “no-go” zones, contaminated docks, and hazardous shipping channels were transformed into welcoming public spaces. In today’s era of frequent and intense heat waves, harbor baths have taken on a new role: they are not only places for swimming, but essential pieces of climate-resilient infrastructure. By offering city harbor swimming, these spaces help cool the urban environment, provide relief during extreme temperatures, and reconnect people with their waterfronts. Copenhagen is a leading example of this transformation, a city that has turned once-toxic harbor waters into a cherished public amenity.

Copenhagen: the blueprint

If there’s a capital of the harbor bath movement, it’s Copenhagen. The Danish capital’s waters were once so polluted that the idea of swimming in the harbor was laughable. By the 1980s, industrial waste, untreated sewage, and stormwater runoff had turned the city’s blue spaces brown. But a series of ambitious projects, including a massive investment in sewage treatment and stormwater management, transformed the harbor into one of the cleanest urban waterways in the world.

In 2002, Copenhagen opened its first modern harbor bath at Islands Brygge, designed by Danish architects JDS and BIG. It featured five pools: two for lap swimming, two shallow pools for children, and a diving pool with platforms. Its angular wooden decks, bright lifeguard towers, and sweeping views made it an instant icon. The water is tested daily in summer, and only when the quality is safe are the gates opened.

The success of Islands Brygge led to a wave, quite literally, of new facilities:

Svanemølle Beach and Bath — Located slightly north of the city centre, this beach-meets-bath offers wide sandy areas alongside designated swimming zones.

Kalvebod Bølge (Kalvebod Wave) — A dynamic, undulating boardwalk opposite Islands Brygge, designed for both swimming and lounging. It’s as much an architectural sculpture as it is a bath.

Fisketorvet Harbour Bath — Nestled by a shopping mall, this bath offers enclosed pools that are perfect for families, plus easy access for lunch or ice cream after a swim.

Copenhagen’s model has inspired cities worldwide. Its success lies in three pillars: uncompromising water quality standards, bold design, and the idea that swimming should be free and democratic.

Scandinavia’s ripple effect

Ribersborgs Kallbadhus, Malmö, Sweden

Perched at the end of a historic wooden pier on Ribersborg beach, Ribersborgs Kallbadhus, affectionately known as “Kallis”, has been a cherished Malmö institution since 1898. The open-air bathhouse is defined by elegant simplicity: separate male and female sections, each with two saunas and a warm tub, plus one mixed-gender sauna. Devoted to tradition, it blends rustic design with year-round resilience. A seaside café and restaurant invite visitors to linger, while sun decks and plunge pools offer a tactile connection to the sea even in winter’s chill.

In 2009, renovations added a new sun terrace and land jetty; in 1995, the bathhouse was officially declared a protected historic building. Kallis also evolves culturally, hosting occasional “Queer Kallis” evenings that welcome all identities, dismantling gender separations in a gesture of inclusivity. Locals and travelers alike relish the shock of cold-water immersion followed by sauna, an exercise in endurance and community. The bathhouse’s enduring appeal stems from its ability to offer a dignified, democratic, and embodied experience of water, rooted in regional self-care and togetherness.

Sørenga seawater pool, Oslo, Norway

In Oslo’s revitalized Hafen district, the Sørenga Seawater Pool has redefined waterfront leisure. Embedded into the rugged Oslofjord coastline, the pool offers a sheltered yet open-air marine swimming. A long wooden jetty, part sunbathing platform, part access point into the saltwater, invites both leaping and lounging. Surrounded by minimalist modern housing and promenades, the facility is more than a swimming spot; it’s a seamless civic amenity embedded within a residential neighborhood. Water is drawn from the fjord, filtered to ensure swimmer safety without losing the sensory punch of the brine, while the site’s clean lines and natural materials evoke Norwegian design principles: craft, clarity, context. In winter, the pool remains open, often attracting hardy, some might say curious swimmers chasing the Nordic cold-water buzz. The site embodies Oslo’s commitment to integrating natural systems into urban life, encouraging coastal access while maintaining ecological stewardship of the fjord.

Allas sea pool, Helsinki, Finland

Perched beside Helsinki’s Market Square, Allas Sea Pool is a masterclass in Nordic urban craft. Opened in 2016, the floating marine spa comprises three pools built as a sculptural wooden deck atop the Baltic Sea, accompanied by multiple saunas, a café, and rooftop terraces. One pool holds heated fresh water (~27 °C), another is UV-filtered seawater drawn from the archipelago, and a third, the children’s pool, is seasonal. The design by Huttunen–Lipasti–Pakkanen is both functional and poetic: treated spruce surfaces blur the boundary between deck and sea, wind-protective forms frame the horizon, and city vistas unfold from every vantage. Allas is open year-round, embracing sauna-and-ice-swim rituals, and hosts music events, wellness classes, and social gatherings. The site succeeds at multiple scales: wellness hub, architectural landmark, and cultural instigator. For locals and visitors, it’s an accessible locus of relaxation, fitness, and conviviality that bridges urban and marine domains.

Together, these Scandinavian pools illustrate a regional ethos: simple architecture, nature-first design, inclusivity, and a willingness to formalize what was once informal (cold plunge, saunas, sea bathing) into robust public infrastructure. Each bath offers its own flavor: historic charm in Malmö, fjord-side modernism in Oslo, wellness spectacle in Helsinki but all speak to the same quietly radical ambition: to make urban waters not just clean, but beloved.

The Badeschiff: continental Europe joins in

As the idea gained traction, harbor baths began popping up in cities across continental Europe. For example the Seine has recently become a popular spot for urban swimming, attracting locals and visitors alike who are eager to enjoy the city from a fresh perspective. In Berlin, where the River Spree flows through the heart of the city, swimming in the natural water is still unsafe due to pollution. But that didn’t stop Berliners from reclaiming the waterfront in their own inventive way. The Badeschiff (“bathing ship”), opened in 2004, is essentially a giant floating pool set within the river. Converted from an old cargo container, its turquoise water offers a stark contrast to the dark Spree, with views of the iconic Oberbaum Bridge and Berlin TV Tower in the background.

The Badeschiff is not just a pool; it’s a cultural venue. In summer, it hosts open-air yoga, live DJ sets, and film screenings. In winter, it transforms into a floating sauna and wellness space. By physically separating swimmers from the river while still immersing them in the urban waterfront experience, the Badeschiff represents a creative compromise: safe, clean swimming without waiting decades for full river restoration. It also signals Berlin’s knack for adaptive reuse, turning industrial relics into beloved public spaces. Though some critics lament the lack of direct water access, others see it as an elegant first step toward the long-term goal of a swimmable Spree.

Challenges and the future

Harbor baths are, above all, public spaces that cut across social lines, offering free or low-cost access to health, leisure, and a sense of shared ownership of the city’s water. They encourage active transport, as most of them can be easily reached by bike or on foot, and foster vibrant, mixed-use communities. In Copenhagen, it’s common to see office workers taking a lunchtime swim, teenagers practicing dives, and retirees doing leisurely laps in the same space. This mingling is part of their charm and a key element of their social sustainability. Yet as urban harbor baths gain global popularity, their growth faces complex technical, environmental, social, and political challenges. The vision of slipping into crystal-clear water in the middle of the city is compelling, but maintaining these spaces as safe, accessible, and ecologically sound requires ongoing commitment and investment.

Harbor baths in a сhanging сlimate

As urban harbor baths gain global popularity, their expansion faces a set of intertwined challenges, technical, environmental, social, and political, that will shape their future. The concept might seem idyllic, slipping into crystal-clear water in the middle of the city, but the reality is that keeping these spaces safe, accessible, and ecologically viable is far from effortless.

1. Water Quality and Pollution Control

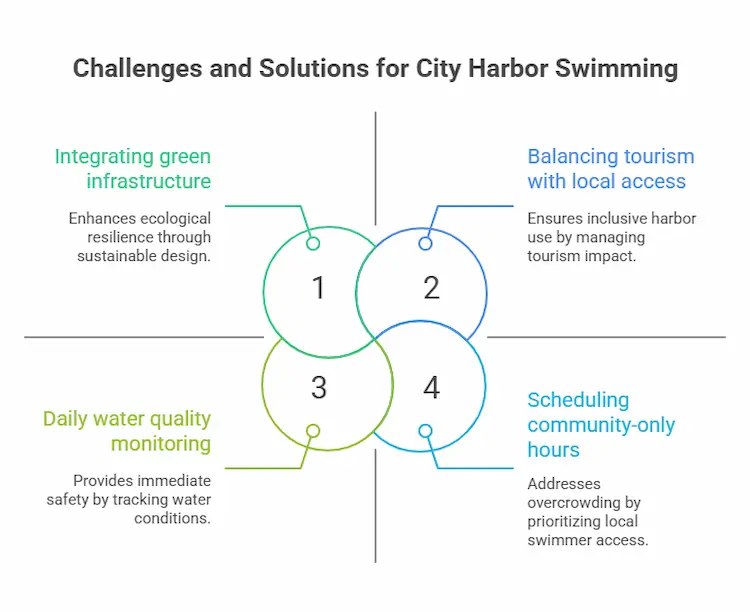

Maintaining water quality remains the top challenge for city harbor swimming. Cities with historic industrial ports face lingering contaminants, and heavy rainfall can spike bacterial levels, making swimming unsafe. Copenhagen monitors water daily and manages stormwater with retention basins, setting an example, but other cities must invest continuously to keep their harbor baths clean and usable.

2. Climate Change and Extreme Weather

Climate change threatens harbor baths through rising sea levels, stronger currents, and longer warm seasons that fuel harmful algal blooms. Cities must design resilient structures, use corrosion-resistant materials, and integrate green infrastructure like wetlands to filter runoff, ensuring that city harbor swimming remains safe and enjoyable despite extreme weather.

3. Balancing Public Access with Tourism Pressure

Harbor baths thrive on open, democratic access, but tourism can crowd local swimmers and strain lifeguard teams. Cities manage this by zoning quieter areas, scheduling community-only hours, and carefully balancing local use with visitors, keeping city’s harbor swimming inclusive while handling high seasonal demand.

4. Ecological Stewardship

Human activity in urban waterfronts can disturb ecosystems, but well-designed harbor baths can enhance local ecology. Integrating native planting, underwater habitats, and circulating water systems allows city harbor swimming to coexist with thriving biodiversity, turning leisure spaces into environmental assets.

The future of city harbor swimming

Despite challenges, harbor baths have a bright future if cities adapt. Hybrid designs will merge natural swimming zones with architectural features like floating wetlands, while sensors provide real-time water-quality data and modular units allow facilities to expand or adjust to sea-level rise. Integrating harbor baths into climate-resilient city plans turns them into green-blue infrastructure that manages stormwater, supports biodiversity, and strengthens social cohesion. From Copenhagen to Toronto, the goal is to make city harbor swimming a standard civic right. Success depends on maintaining water quality, managing access, and keeping ecological promises. Done right, harbor baths become more than leisure spots; they transform urban waters into everyday spaces where residents truly live with the water.

The best harbor baths are not monuments; they are everyday spaces, used by everyone from the morning lap swimmer to the evening picnic crowd. They prove that environmental restoration can be tangible, joyful, and woven into daily life.

On that same Copenhagen morning, as the sun climbs higher and the chatter around Islands Brygge grows louder, it’s easy to forget that two decades ago, the water was too toxic to touch. Today, it’s a living reminder that with the right mix of political will, design ambition, and community trust, cities can reclaim their blue spaces and invite the world in for a swim.