A Global UN Study Reveals the Hidden Costs of Coal Extraction

Coal mining has long been a cornerstone of industrialization, powering economies for centuries. It has been – and in some regions remains – an essential source of energy. But what happens to the land after the coal is gone? The environmental aftermath of coal mining is only now being fully understood. A team of United Nations researchers and academic experts has conducted the first comprehensive global meta-analysis of soil contamination near coal mines — and the findings are alarming. As the world shifts toward cleaner energy sources, understanding the long-term impacts of coal extraction on soil, water, and climate has become more urgent than ever.

An interview with the author of the article is here.

The scope of the study

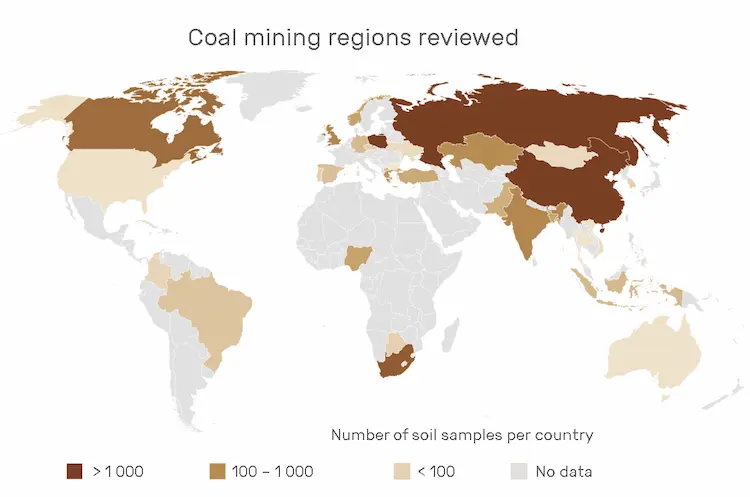

Published in the journal Environmental Earth Sciences, the research synthesizes data from 13,925 soil samples across 55 coal mining regions worldwide, excluding only Antarctica (where coal exists but remains unmined). By analyzing decades of studies, the team identified consistent patterns of soil degradation linked to coal extraction, offering policymakers a roadmap for land rehabilitation.

Key findings: how coal mining transforms land

Toxic legacy of metals

The study found potentially dangerous concentrations of lead, arsenic, cadmium, and mercury, in certain cases higher than safe thresholds in some regions.

Acid drainage: a silent crisis

When exposed to air and water, coal waste generates acid mine drainage (AMD), which acidifies soils and leaches metals into groundwater.

Carbon loss and soil sterilization

Mining disrupts soil structure, stripping organic carbon and microbial life. In Germany’s Lusatia region, soils take decades to recover even with remediation.

Global inequities

Developing nations face disproportionate harm. In India’s coalfields, spontaneous coal fires have burned for decades, compounding pollution.

Why this matters for the energy transition

As countries phase out coal, the study warns that unremediated mines could undermine climate goals. Contaminated lands lose capacity to sequester carbon, and degraded soils threaten food security when repurposed for agriculture.

Solutions: what works?

The team highlights 3 proven strategies:

- Active remediation (e.g., adding lime to neutralize acidity).

- Phytoremediation (using plants like willow trees to absorb metals).

- Policy levers (e.g., Germany’s mandate for mining firms to fund cleanup).

The road ahead for the environmental aftermath of coal mining

The study shows that land restoration alone isn’t enough. Communities need support to avoid living with pollution and decline. Researchers call for a just transition. They stress the need to clean the land and protect people’s health and future. A fair recovery must include clean water, safe soil, and new jobs. Without this, mining regions will continue to suffer.

For policymakers, the message is clear: Coal’s end must include healing its beginnings.

The open access scientific article is here.